SANTA SEVERINA AND THE DIOCESAN MUSEUM

Santa Severina does not exist. Or rather, there is no historical or hagiographic figure of that name. There is not even a story, a fable, a legend, anything to strengthen the memory. However, there is a town of that name; and there are scattered here and there, from the Emilia to Sicily regions through Apulia, some religious effigies, venerations, transient traces of cults that now appear as faded ghosts of rituals set by the people and not by the hierarchy. The people, who build the city and the temples, identify more with the title than with history. History is not authentication, if anything it is research according to the etymology of the name; research which has long been inactive in the soothing familiarisation of centuries and of many names of corners of our wonderful country. We must believe in Justinian (Institutiones, 2, 7, 3) when he warns with no irony that nomina sunt consequentia rerum? Apparently no, but he had in mind the naming of all things forced on the first of us to validate our power over all of them: with the not exactly good results.

Santa Severina exists. As an ontological reality, even if it appears almost as a meaning devoid of signifier. Its name is the consequence of what things? Of a city to be, precise, stone ship landed on a tabular cliff, perhaps originally double: one where the Castle is today; the other containing, in blatant conflict of powers in the medieval city, an urban pattern inhabited by a flock sheltered by God’s reassuring presence than the lordling of the day. The flock in their heart, maybe always knew it more than the scholars chasing a closed circuit erudition, therefore, unable to start on the path of knowledge, and of history. He always knew that this is not a medieval town, although it closely resembles one. It is a Roman city; perhaps Brutia; even prehistoric if only you look back toward Mount Fuscaldo, the cliff, this time sharp, that dominates the west. Whatever you want it originating from, its originality is the result of a conscious choice. There are evident traces in the Baptistery: Built with reclaimed material of a Roman and late Roman settlement, its early middle Ages makes one ask today: where are the other Roman reminiscences? There are, and for those who know where and want to look inscriptions on stone, for example. One need not look any further than the Sacred Art Museum to see an indisputable example. The Byzantine presence has somewhat stifled this soul, and perhaps the other Lombard soul, of which very few speak but that had to be present to some extent, using it where possible for other purposes. The building of the Baptistery with its solid inner ring of columns, where classic mixes with barbaric in a strikingly powerful set, is the demonstration of this syncretic embrace. Elsewhere in the city, culture and art specialize, they follow patterns and currents of ideas, interpret the territory observable from the top of the cliff, and from the bottom of the socio-economic interrelations developed in the years of its documentary history between the Ionian Sea and Silas, without imperfections.

Santa Severina will exist. No longer just a name and container, but something else again led by passionate new times and events. Its people can hold the memory of its legendary settlement, not expressed but felt in the fibres of its being, building old named shells with new content where it can reflect itself in its cultural maturity. What is a castle if not the continuation of a masterful idea of power in the making, where everyone allocates their representation? Sometimes even grim, but as is known, the spirit of the times is fickle, only in the end one can certify its quality. What is a museum of sacred art if not the tangible apotheosis of a community capable of recognizing itself in the depths of its previous existence? Before I called it the flock, it is no longer a flock: the quality of the seed that it has spread around, through the firm and at the same time humble personality of its editor, Bishop Giuseppe Misiti, makes it a certainty of an existence without uncertainties. The Muses, from which Museum, were the daughters of Mnemosyne, of memory, today restored to its actual occurrence, here and now. There are no properties to see: but rather to discover, in which to find part of one’s cultural horizon. From the seed the semantics; from the object the symbolic narrative. Everyone will be able to re-build its own dimension. Only in this way from Santa Severina meaning becomes significant, for the time necessary to our being. That is forever. Such is the certainty of the future: unwritten, but already encoded.

(Taken from ‘Museo Diocesano Di Arte Sacra Santa Severina – Catalogo delle opere’, text by Ilario Principe, aprile 2014)

COLLECTIONS

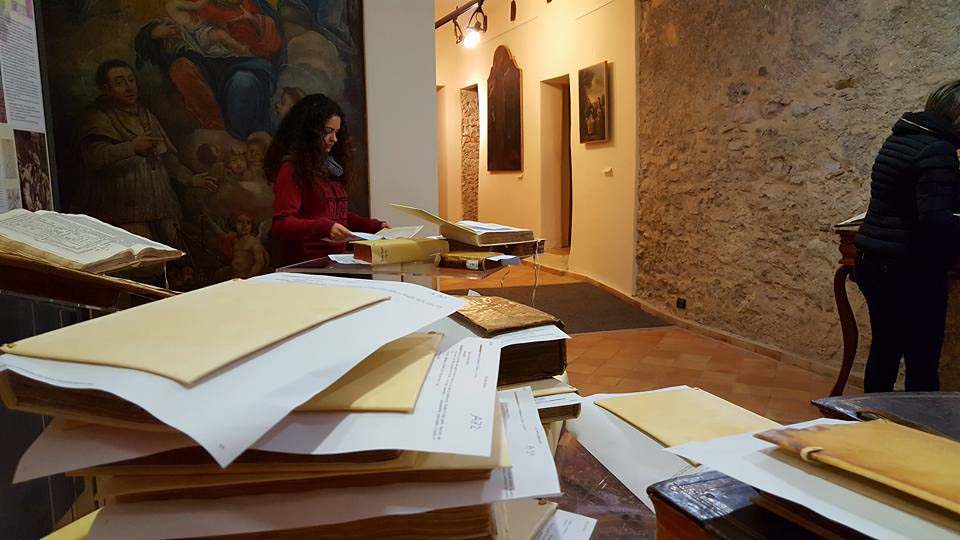

The Diocesan Museum of Santa Severina, founded on the initiative of H. E. Monsignor Archbishop Giuseppe Augustine VM and edited by Mons. Giuseppe Misiti, was opened in 1998, housed in the beautiful Archbishop’s Palace flanking the Cathedral, overlooking Piazza Campo in front of the castle. In the historic building, in addition to the museum, are placed the Diocesan Historical Library and Diocesan Historical Archives thus forming a unique cultural center that is unique throughout Calabria and southern Italy.

The Diocesan Museum collects essentially the historical and artistic treasures of the Cathedral and the Bishop’s Palace. Both unfold chronologically from the Early Middle Ages to the twentieth century andoutstandingly tell the story of the local church and the bishop’s seat, which, in a region like Calabria, where the ecclesiastical institutions have been some of the most deep-rooted and less susceptible to changes, merges with the history of the city. Furnishings, vestments, paintings and sculptures, therefore, become themselves a reflection of the development of the city’s culture over the centuries and, with particular reference to their specific forms of art, also allow you to keep track of the of the regional art history.

The exhibition, as it has been organized so far, being the Diocesan Museum of Santa Severina not yet in its final draft, is divided into distinct thematic sections but still closely linked to the existence of nodal points, regarding both the artefacts and teaching, which allow connections between the sections themselves under the historical, artistic and iconographic aspects. The first section is an actual tour dedicated to the historical, architectural and urban design evolution of the city through the places of worship that still exist in it and, therefore, great importance is given to the Cathedral and to the “Baptistery”. Along with floor plans and placards, marble findings coming from these buildings are exhibited, recovered in recent restorations, and an important addition is trapezoidal capital of the Byzantine period and a fragment of a plate with a bearded head of a saint probably from between the late thirteenth and early fourteenth century. This fragment was part of a larger decoration – maybe an Apostolate. – Of which there are other plates found by Pino Barone in the Cathedral, re-used on the altar of St. Leo and precisely in the two sidepieces of the broken pediment. From the church of Our Lady of Sorrows, the first cathedral of Santa Severina comes the bell signed by “Master Andreas”, also dating from between the thirteenth and fourteenth century and for this reason, it is a unique record. From one of these churches also comes a wrought iron chandelier that can seem of probable late medieval artisanship.

The second tour or section is dedicated to the records of the art of the silversmiths and goldsmiths and consists of a large part of the so-called “Treasury of the Cathedral,” one of the richest and most precious of Calabria, therefore one of the most interesting and perhaps the most important of the Diocesan Museum. There is a beautiful cope fastener made of gold, enamel, pearls, ornamental stones and glass paste which is production of the late Angevin era of the South: It represents a blossoming flower seen from above and contains evocative symbolic Christological references, clearly explained by an inscription that runs on the base. Another extraordinary pin is that of Archbishop Charles Berlingieri (1679-1719) entirely open-worked with floral motifs embellished with ornamental stones and it is the work of Neapolitan silversmiths working when the bishop occupied the archbishop’s chair in Santa Severina. Among the many liturgical furnishings displayed, certainly suitable to represent the evolution of rites and forms of art associated with them, a pair of patens also emerges with the bottom engraved with a depiction of the Last Supper and a large silver chalice decorated with images of the Passion of Christ. Among the relics, St. Anastasia’s arm, silver artefact that holds the relic which tradition says was donated by Robert Guiscard. It is composed of a base made in the last decade of the seventeenth century by a Neapolitan silversmith by order of Antonio Gruther († 1733), lord of the town, and of an arm during the episcopate of Bishop Nicola Carmine Falcone (1743-1759). Among the votive various gold jewellery, pearls and precious stones are displayed some of which are certainly providing insight into the art of the South and of Calabria between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The full-length silver statue of St. Anastasia was made in 1792 by a member of the Baccaro family – in fact, the punch SB is printed on the metal foils which has been interpreted as belonging to the workshop of Luca Baccaro. It introduces the section dedicated to the city’s patron saint, St. Anastasia in fact, where other works of art that represent her are displayed. The beautiful painting by Fabrizio Santafede, Neapolitan artist of the late Mannerism, is included. It is dated between the second and third decades of the seventeenth century and shows the naturalistic inclinations well absorbed with Lombard artistic interests well absorbed in the artistic culture of the painter.

The painting section collects many of the seventeenth and eighteenth century records, among which are: The Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine of Alexandria a copy of Correggio, still displayed on the altar of the chapel of the Bishop’s palace, the Presentation of Santa Rosalia to Christ a Dick van copy and the Trinity with the Dead Christ which is derived from a composition of Giaquinto. Among the works most closely related to the territory, however, we highlight two eighteenth century paintings by Francesco Giordano, depicting the Last Supper and the Washing of the Feet, which belong to the decoration of the ceiling of the Hall of the Coat of Arms of the Bishop’s Palace, and another dated 1739 by Domenico Leto with the Pietà venerated by St. Philip Benizi.

Among the sculptures, however, there are several seventeenth century fragments, such as the coping carved with the figure of the Eternal Benedicente, and the two statues of St. Michael the Archangel made one, in 1744 by Bernardo Valentino, Neapolitan artist still little known and whose group of the Madonna delle Grazie of San Giovanni di Gerace is kept in Calabria, and the other, monumental, in 1837 by Vincent Zaffino or Zaffiro, remarkable artist from Serra San Bruno.

Very rich, finally, is the section that shows the liturgical vestments. It holds rare examples of complete vestments for pontificals made of very valuable fabrics, both laminated and worked as damasks and velvets. The interesting silks, probably made with the Catanzaro technique, stand out, dating from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but also other pieces coming from Venice or Lyon and beautiful embroidery. The perfect preservation of these fabrics make the collection of the Diocesan Museum of St. Severina one of the most important in the South, increasingly in line with the specific timelines due to the presence of the bishop’s coat of arms that have never been transported. The Diocesan Museum of Santa Severina has been enriched by the donation of an interesting collection of archaeological and numismatic finds from Francesco De Luca, a local historian, so there is also a section dedicated to the archaeology of the area. The prehistoric among these findings certainly must be stated, for instance bronze, buckles, pendants and bracelets, Greek and Roman coins, the Encolpion of the Byzantine and medieval era.

(Taken from ‘Museo Diocesano Di Arte Sacra Santa Severina – Catalogo delle opere’, text by Giorgio Leone)